The American Folk Art Museum

The American Folk art Museum

On September 16th 2016 we visited the American Folk Art Museum in Lincoln Square. There we met Nicole Harovturian, one of the institution’s museum educators. Nicole began by asking us what we expected to see at museum dedicated to folk frt. She used that question to lead into a discussion on what folk art means. The term folk art does not have a concrete definition; the working definition at the American Folk Art Museum is art created by someone with out formal training. This is not to say the artists whose work is exhibited at the museum have not received training. Their education could have come from family, friends, peers, instructional videos etc. Operating with this definition gives the museum a broad array of artists to choose from when curating exhibitions and allows them to avoid more problematic terms like outsider art or naïve art.

The exhibition “Fever Within” featured the work of Ron Lockett from Bessemer Alabama. Lockett learned about art from his cousin Buck, his great aunt Sarah Lockett and Bob Ross. Nicole began with a piece titled “Trap”. She began by using visual teaching strategies, an enquiry based approach meant to illicit information from a group based on what they see. After everyone in our group took a turn making observations, we established that the piece was an assemblage of old, rusty, corrugated sheets of metal, netting, cut aluminum branches and paint. The piece depicts a buck trapped in the remnants of big industry. Lockett lived in a former industrial town. Discarded metal, broken down equipment and abandoned structures were part of his ever day life. In the top right corner a circle was cut out of the metal and inside the circle was a landscape painting. Nicole followed this discussion with a short lecture on Ronald Lockett. Receiving some key biographical information on Lockett gave us a more insight into his work and into the symbolism he used.

The second piece we discussed, “Sarah Lockett’s Roses”, was a quilt like patch work of roses made from cut metal. Nicole informed us that Sarah Lockett was a quilter and supportive of Ronald’s art making. She then handed out some samples of quilt squares bringing touch into the experience. Seeing and feeling the quilt helped us make connections between quilting and Ronald’s work.

Nicole took a different approach with the third piece we looked at, The Fever Within. She handed out paper and pencils and asked everyone to write one complete sentence about the piece. We then shared our sentence with the person sitting closest to us providing us an opportunity to share our descriptions in a in a more personal conversation. We then chose three words from our sentence that we believed to be the best words to summarize the work and shared it with the group. We repeated the process again but this time selecting one word.

We ended on a piece, which was not made by Lockett. Hanging wooden ex-votos made by unidentified Brazilian artists. The ex-votos were wooden body parts, which hung from the ceiling. Originally they were meant to be hung in a house of miracles, where people could come and pray. The reason she showed us this piece was to present us points of connection between Locket and other artists. Including works from other artists helps put Lockett’s work in a greater artistic context and consequently gives visitors a better understanding of Lockett.

The American Folk Art Museum is an excellent area specific Museum. The exhibitions are tastefully curated to give agency to artists and art forms that are often overlooked and under-appreciated. The labels on the pieces provided the essential information including title, materials and year created, as well as a paragraph or two of information on each work. Nicole was genuinely enthusiastic and interested in the work she was presenting making the educational experience that much more enjoyable.

Tommy Mavra

The Rubin Museum of Art

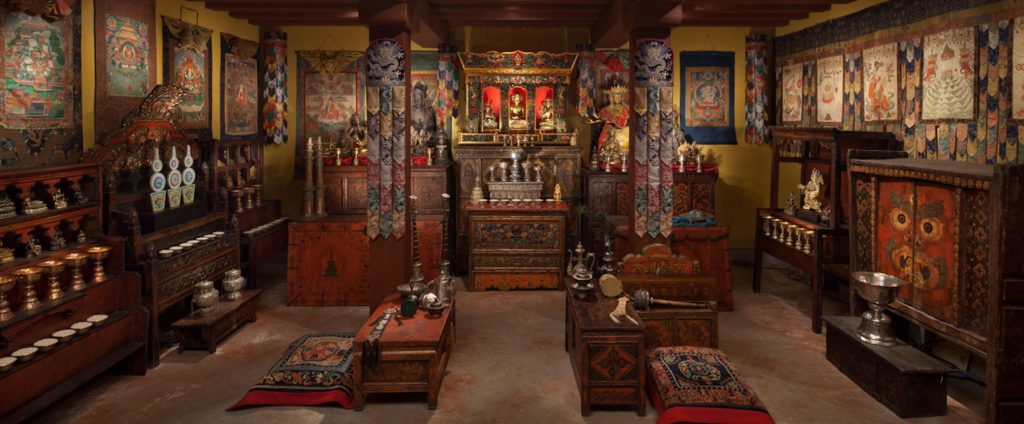

Focusing on cross-cultural connections, the Rubin Museum of Art showcases art of Himalayas and neighboring regions including India. On September 8, 2016, our Museum Education class visited the museum. We had the pleasure of meeting Nicole Leist, Manager of Academic Programs, who gave us a tour of the museum. The experience with Nicole was very enjoyable and productive. The museum has 6 floors; the second-floor gallery displays objects from the permanent collection, introducing audiences to Himalayan art. As Nicole explained, the intention behind the second-floor gallery is to provide audiences with the background knowledge and the language to learn about art in this region. The third floor is dedicated to more specific forms of art, and the fourth floor is an interactive space, where many of the museum programs are held. During the tour, there are two works that are very memorable to me: the Vajrayogini statue and a recreation of Tibetan shrine, which were also two main works explained by Nicole.

Nicole began the tour by asking about our majors and area of focuses as artists and art historians. I very much enjoyed the educational strategy employed by Nicole when she showed us a Tibetan Buddhist, the sculpture of the deity Vajrayogini, who represents feminine energies (http://rubinmuseum.org/blog/march-womens-history-month-art).

To unpack the complex and the multi-layered symbols inherent in Buddhist culture and the sculpture, Nicole first encouraged us to engage with artworks through direct and visceral experiences. Giving a general idea about a piece first, she would then ask us to describe the artwork, which created a conversation between her as an educator and us as the audience. As for the Vajrayogini deity sculpture, after telling us that the artwork would challenge some of the western perspectives on Buddhist deities, Nicole asked us to point out the “unusual” components in the sculpture. She then began to contextualize the piece in a witty and expressive way by using straightforward, yet vivid language. For example, she referred to the deity as a “sexy and scary teacher” and a “tough lady” when discussing the relationship between the role and the energy of this deity. Nicole employed a sense of humor, she also made interesting and lucid analogs when experiencing complex and confusing topics. An example was when she raised the question “why does a Wrathful deity seem to be horrifying?” She described them as “angry” deities before comparing the deity with a super-powered mother, who would show an intense yet fierce energy when pushing away a truck in order to save her child. Through the educator’s humorous and vivid storytelling, I was able to comprehend her teaching immediately and joyfully, which also left a strong impression on me about the work thus fulfills her pedagogical goal as an educator.

As a culturally specific institution, the Rubin’s educators such as Nicole, who is truly interested in the artworks shown at the museum, and is happy to engage with audiences, helped me gaining knowledge about the region, religion and the art. At the same time, some of the institution’s interactive exhibitions and guided tours also provide audiences with multi-sensory experiences. For example, there is a recreation of Tibetan shrine inside of the museum.

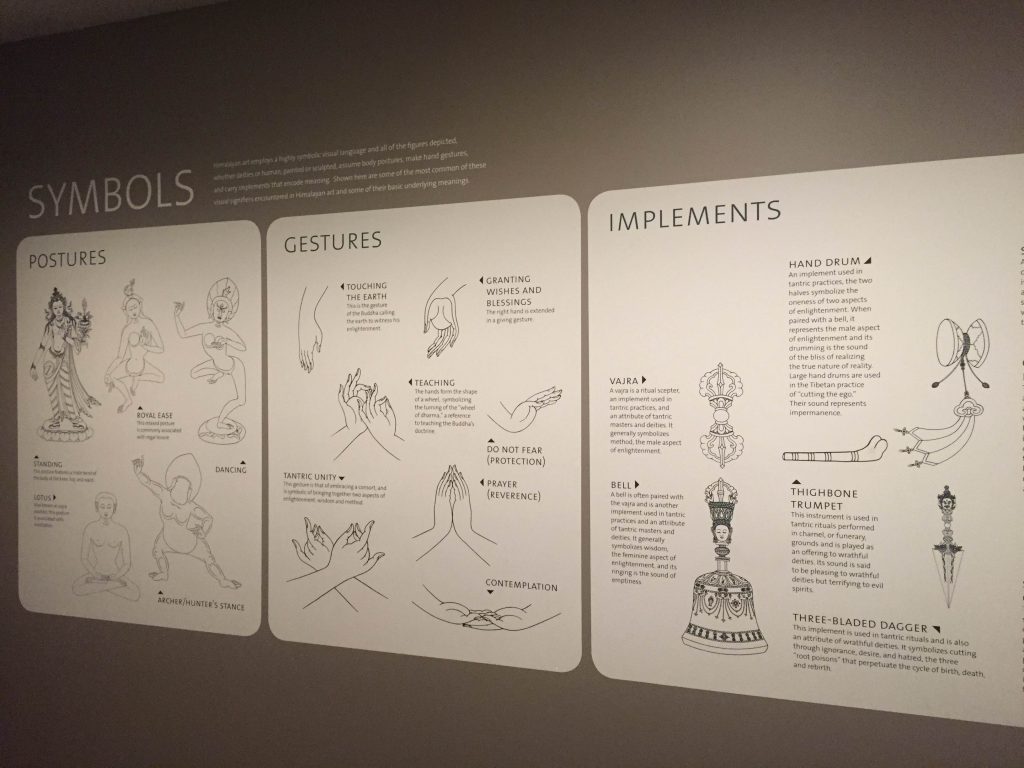

Audiences are able to engage with the space through visual, auditory, and even olfactory experiences, which as if leading them into the actual environment and the culture. This kind of interactive dynamic is evident in The Looking Rubin Guide, a brochure with beautiful drawings showing Figures, Postures, Gestures and Implements in Buddhist and Hindu art. With the guide, audiences are able to identify and learn about he fundamental symbols viewing the artworks. The information and the guide are also displayed on wall panels adjacent to specific artworks to illustrate some important symbols.

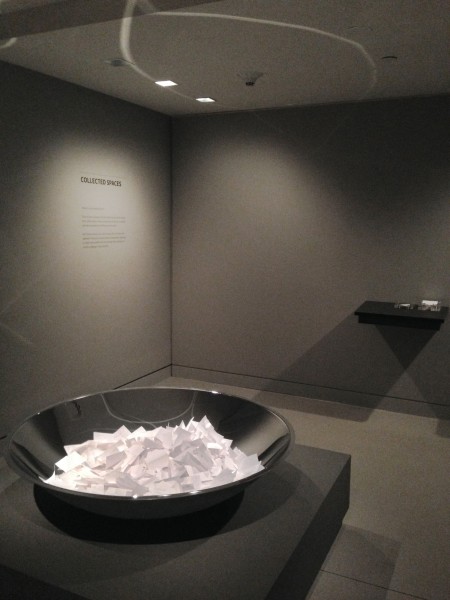

Upon viewing the illustration, I found myself beginning to mimic the hand gestures. The brochure invited me to recognize common symbols and important figures in Buddhist art. Another interactive element at the Rubin is the installation “collected Spaces,” which is a large container with audiences’ notes created when they make a wish.

The wall text for the “space” opens up with a question “where is your sacred space?” As appealing and welcoming as the wall text is, the space itself is designed tranquilly and intimately, encouraging the audiences to contribute their notes, but more importantly to share their personal experiences with the institution. Thus the audiences no longer receive an isolated and merely didactic experience, but also shared stories among other audiences, as well as the connection with the museum.

I enjoyed my experience at the Rubin Museum, with educator Nicole Leist. I expanded my knowledge of the role as an educator and strategies that could potentially maximize audiences’ comprehension in the context of a culturally specific museum. As an audience, I would like to visit the museum again and participate in more of the educational programs and public programming at the Rubin Museum.

Review of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture

Wall Street Journal Critique of Brooklyn Museum

What Would You Say #5

https://www.instagram.com/p/BKnnVP1DmO-/?taken-by=bcmuseumed

What Would You Say #4

https://www.instagram.com/p/BKVvgB0gwNH/?taken-by=bcmuseumed

What Would You Say #3

https://www.instagram.com/p/BKBBsl8gTyv/?taken-by=bcmuseumed

“What Do You See in Art?” A New York Times article

Students, I think all of you might find this article interesting, particularly as we begin our journey to better understand the role of museums and education!

What Would You Say #2

https://www.instagram.com/p/BJvHzOqg5j5/?taken-by=bcmuseumed